Illustration: Fabrizio Lenci

In 2020, the worldwide coronavirus pandemic put the brakes on Hannah Wardill’s analysis. As nationwide lockdowns loomed, Wardill — then a postdoc on the College of Adelaide, Australia — left a analysis challenge within the Netherlands and flew dwelling earlier than journey bans kicked in. On the time, she feared this may hurt her probability to win grants, however within the years because the pandemic, Wardill’s profession has flourished. She nonetheless doesn’t have a everlasting tutorial place, however leads her personal analysis group in supportive oncology on the College of Adelaide. “The influence of COVID has actually lifted,” she says.

Wardill just isn’t alone. In 2020, respondents to Nature’s first international survey of postdoctoral researchers feared that COVID-19 would jeopardize their work (Nature 585, 309–312; 2020). Eighty per cent mentioned the pandemic had hindered their potential to hold out experiments or acquire information, greater than half (59%) discovered it tougher to debate their analysis with colleagues than earlier than the disaster, and almost two-thirds (61%) thought that the pandemic was hampering their profession prospects.

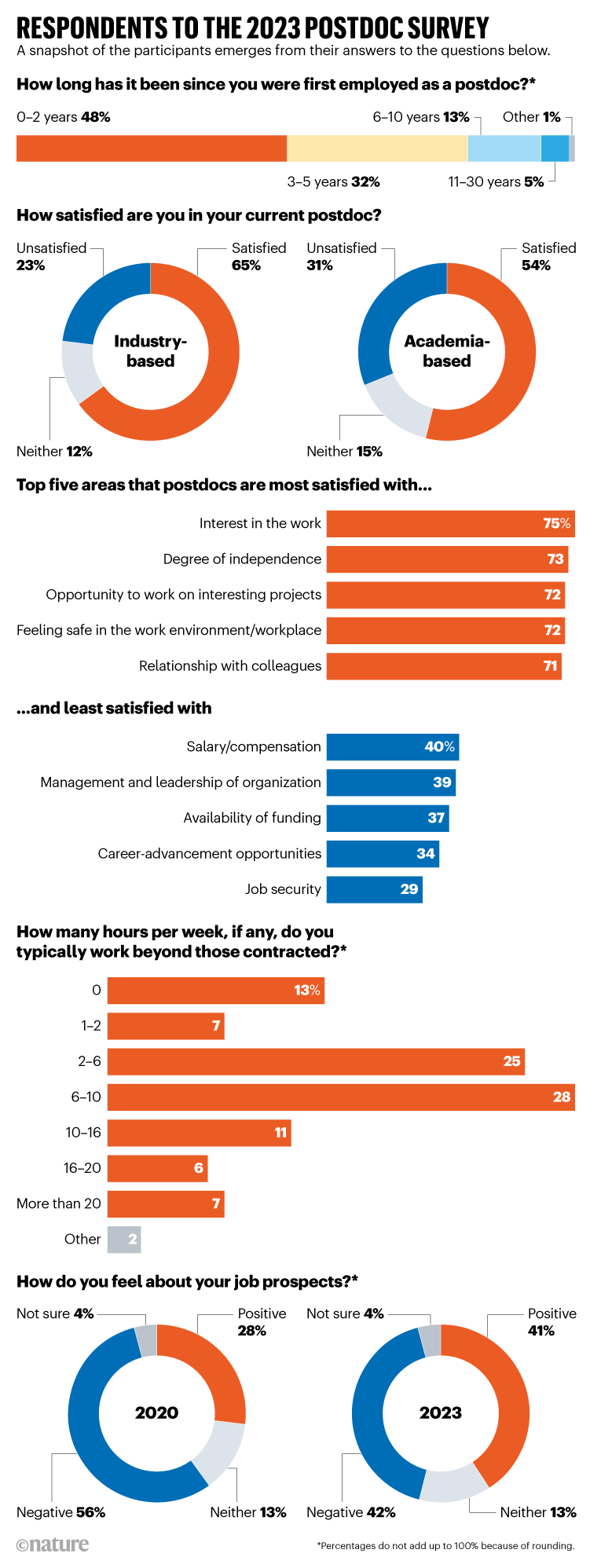

That outlook has modified, based on Nature’s second international postdoc survey, carried out in June and July this yr. Now solely 8% of the respondents (see ‘Nature’s 2023 postdoc survey’) say the financial impacts of COVID‑19 are their largest concern (down from 40% in 2020). As a substitute, they’re again to worrying in regards to the traditional issues: competitors for funding, not discovering jobs of their fields of curiosity or feeling strain to sacrifice private time for work. General, 55% say they’re happy of their present postdoc, a slide from 60% in 2020. This varies by geography, age and topic space. Postdocs aged 30 and youthful usually tend to be happy (64%) than are these aged 31–40 (53%). Biomedical postdocs — who make up barely greater than half of the respondents — pull the typical down, as a result of solely 51% say they’re happy with their jobs.

Diminished concern about COVID-19 just isn’t the one constructive development. The typical variety of time beyond regulation hours has fallen, with 13% saying they don’t do any time beyond regulation (up from 9% in 2020). Additionally, extra postdocs are reporting an applicable stage of assist for psychological well being and well-being at their establishments than beforehand (22%, up from 18% in 2020; see ‘Small features’), and a great work–life stability (42%, up from 36% in 2020). However the largest shift is within the proportion of postdocs who really feel optimistic about their future careers — swelling from 28% of respondents in 2020 to 41% in 2023 (see ‘Respondents to the 2023 postdoc survey’).

Underappreciated, however optimistic

General, nonetheless, the information proceed to color postdocs as academia’s drudge labourers: overworked, underpaid, appointed on precarious short-term contracts and missing recognition for his or her efforts. Patterns of discrimination and harassment haven’t modified since 2020. One-quarter of respondents report having skilled both, or each, of their present or earlier postdoc. Respondents spotlight bullying as the commonest type of harassment — encountered by 52% of those that had skilled discrimination or harassment – with managers, supervisors or principal investigators being essentially the most generally cited perpetrators.

US postdocs on strike: how will calls for for larger wages be met?

“Essentially, I don’t suppose the postdoc expertise has modified,” says Michael Matrone, affiliate director of the workplace of profession {and professional} improvement on the College of California, San Francisco. “What I feel has modified, catalysed by the pandemic, is a larger consciousness of and intolerance for the oppressive and exploitative techniques that exist in academia.”

Julia Sanchez-Garrido feels extra optimistic now than three years in the past. Again then, she was certainly one of 9 million Londoners making an attempt to remain 2 metres other than different individuals. She was additionally fighting loneliness and worrying about not having the ability to entry her bacteriology lab at Imperial School London. “I feel 2020 was only a very dangerous yr,” she says. “All the things was halted. It was not possible to get lab gear. You had no social life.”

Now, with a couple of yr left of her present postdoc at Imperial, her largest fear is job safety, however it’s tempered by a rising realization that there are various fulfilling choices to contemplate. Though she want to keep in academia, she has seen many colleagues transfer to {industry}. “I feel persons are happier as a result of they know that they’ll transfer out of academia, and it’s not a failure,” she says.

Like many postdocs in Nature’s survey, microbiologist Julia Sanchez-Garrido feels extra optimistic than she did in 2020.Credit score: Julia Sanchez-Garrido

This yr’s survey contains the views of industry-based postdocs for the primary time. Though the proportion of those respondents was too small (7% of the overall) to do a head-to-head comparability with these in academia, their solutions recommend that postdocs in {industry} have a extra constructive outlook: for instance, 65% describe themselves as happy, in contrast with 54% in academia. They’re additionally higher paid (23% earn between US$80,000 and $110,000 yearly, versus 5% in academia), higher in a position to keep away from time beyond regulation fully (20%, in contrast with 12) and higher in a position to save the sum of money they need (29% versus 19%). They’re additionally extra prone to really feel that their office promotes bodily security (83% in contrast with 74%) and dignity (65% versus 54%).

One respondent, an ecologist who left a postdoc at a North American college earlier this yr for one at a personal environmental group, says she is way happier in her new publish. “The most important factor is that there’s a good probability that my present place will flip right into a everlasting, significant place, with nice wage and advantages,” wrote the ecologist, who requested anonymity as a result of she doesn’t need to bitter relationships together with her former employer. No such guarantees have been made in her tutorial postdoc, she says. Additionally, she now enjoys higher advantages, together with free health club membership, the next wage and an improved work–life stability.

Location issues

Along with variations between academia and {industry}, the survey additionally reveals regional variations. Postdocs primarily based in Africa have been most probably to be dissatisfied with their present place (38%), adopted by these in North and Central America (34%). In contrast, 58% of postdocs primarily based in Europe reported that they have been happy with their present jobs, and Australasia-based postdocs have been the most probably to be happy (68%).

Massive proportions of postdocs in Europe (70%) and Australasia (64%) reported job safety as a trigger for dissatisfaction, whereas these in Africa and South America have been dissatisfied with office advantages, comparable to medical insurance. And regardless of incomes a few of the highest salaries, postdocs in North and Central America are essentially the most dissatisfied with their pay (86% of postdocs in North and Central America earned $50,000 or extra yearly, in contrast with 44% in Europe). Practically two-thirds (62%) of North and Central American postdocs have been dissatisfied (giving their wage a rating of 1, 2 or 3, with 1 being ‘extraordinarily dissatisfied’), in contrast with simply 27% of Australasian and 38% of European postdocs.

Breast-cancer researcher Samyuktha Suresh says greater than half of her postdoc wage goes in direction of lease in California.Credit score: Luci Valentine

Samyuktha Suresh, a breast most cancers researcher at Stanford College in California, moved to the USA one yr in the past after ending her PhD in France. “I’m paid a lot extra as a postdoc compared to my PhD wage in Paris. However I really feel a lot poorer when it comes to how a lot I can afford,” she says, including that greater than half of her postdoc wage goes in direction of lease. “Simply paying US postdocs extra would most likely alleviate plenty of issues,” she provides.

Victoria McGovern, chief technique officer on the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, a personal biomedical analysis funder in Analysis Triangle Park, North Carolina, says that early-career researchers primarily based within the space used to have the ability to purchase a home — one thing that helped to make them really feel settled and mature. However Californian firms shifting into the world precipitated costs to skyrocket out of the attain of junior researchers. Between October 2020 and September 2023, based on the property web site realtor.com, native home costs rose from round $220,000 on common to greater than $400,000.

McGovern says that though the mass lay-offs feared at the beginning of the pandemic didn’t materialize, a hiring disaster in academia has now taken maintain, with labs struggling to fill postdoc posts. “Postdocs are being pulled off into six-figure [industry] jobs that pay higher than school positions, and it’s taking place quick,” McGovern says.

Simply understanding that there’s another path in {industry} may assist to spice up profession optimism in academia, McGovern provides, alongside post-pandemic adjustments to working life and workers’ shifting expectations. “Persons are much more conscious of their very own company. It’s the sense that they don’t seem to be trapped, that there’s one thing that they’ll exit to do to make their lives higher right this moment,” she concludes.

Suresh’s associate left academia for a analysis place at a semiconductor firm in Vancouver, Canada, and infrequently urges her to hunt a job in {industry}. However she is loath to surrender on her dream of a everlasting school place. “I’m optimistic,” she says. “I’m going to strive the whole lot that I can to get an educational place first.”

Retaining the religion

Suresh faces robust odds. In Nature’s 2023 information, 65% of respondents say they need to base their careers in academia, a slight rise from 63% in 2020. That may be a “very regarding” determine, says Paige Hilditch-Maguire, director of alumni and company partnerships at Queensland College of Expertise in Brisbane, Australia, including that it indicators a misalignment between expectations and the fact of the tutorial job market. “This can be very unlikely that 65% will find yourself in tenured or in long-term tutorial positions of their fields.” Most information recommend it’s extra like 20%, and the proportion is even decrease in some disciplines, she says.

A lot of the postdocs who spoke to Nature hope to remain in academia, regardless of understanding the difficulties. Some really feel their probabilities might need improved as extra of their opponents depart for {industry}.

Lab leaders wrestle with paucity of postdocs

Reuben Levy-Myers, who began his first postdoc in neuroscience at College of California, San Diego, in Might, says he discovered the applying course of much less anxious than he had been led to imagine. “Principally, it feels just like the people who have chosen to remain in academia could have a better time than a number of years in the past as a result of there are so few of us left. I fear a couple of downward spiral the place there will not be sufficient postdocs, so not sufficient analysis will get carried out.”

Bruce Weaver, a physics postdoc on the Swiss Federal Institute of Expertise in Lausanne, additionally desires to present academia a go. He’s happier now than he was in 2020 as a PhD pupil at Imperial School London. His pay is sweet, he says, and so is his work–life stability. “You learn articles that suggest that numerous individuals don’t need to be postdocs, however when you’re right here, there’s numerous good issues in regards to the job,” he says.

Others have discovered a way of optimism via partaking in activism that goals to alter the best way postdocs are handled in academia. Postdocs in the USA and elsewhere are banding collectively to battle low pay and an absence of recognition. Prior to now yr, postdocs at a number of US universities have launched into strike motion, and there are ongoing discussions a couple of nationwide postdoc union to spice up their bargaining energy.

Earlier this yr, Tim MacKenzie, a genetics postdoc at Stanford, and others on Stanford’s postdoc council printed a report analysing the poor working circumstances of US-based postdocs on the whole, and at Stanford particularly (see go.nature.com/46ukji1). The report discovered them to be in occupational limbo: neither college students, nor workers.

Seeing others rally behind the report’s message has given MacKenzie a way of optimism. “There’s plenty of work to be carried out. And none of us can do it alone,” he says. “We’re empowered. That’s been one thing that’s actually inspiring for me and offers me a little bit of hope shifting ahead.”